|

Research Interests

My research is diverse but broadly encompasses how humans affect insect communities and subsequently species interactions. To do so, I explore ecological mechanisms underlying both species' and community response to human environmental change, and collaborate with researchers studying a diversity of ecological systems, theoretical disciplines, and applied approaches. In the CU Museum of Natural History I focus on the impacts of human land-use on native bee community ecology, and how natural history knowledge can help inform their conservation. In the Dept. of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, I focus on butterflies, and the impacts of exotic plants on the chemical ecology of multitrophic interactions. Both avenues of research underscore why improving our understanding of biological communities is crucial to mitigate the negative impacts of human-induced environments change. |

|

Chemical ecology of multi-trophic interactions

I am currently collaborating with Deane Bowers (CU-Boulder), Angela Smilanich (UNR), and Nadya Muchoney (UNR), to examine how the incorporation of a novel introduced host plant impacts interactions between herbivores and their natural enemies. A growing body of evidence suggests that the insect immune system plays a vital role in structuring interactions between plants and their insect herbivores, and humans can directly alter these relationships through introducing novel hosts, but also indirectly through host plant-mediated changes in species interactions. Together, we've studied three nymphalid butterfly species: Junonia coenia, Euphydryas phaeton, and Anartia jatrophe, all of which feed on an introduced hostplant, Plantago lanceolata. Specifically, we are exploring how this novel host shift impacts the sequestration of plant secondary metabolites, immune function, and defense against both pathogens and parasitoids. We've explored broadly variation in host plant secondary metabolites and their sequestration by herbivores (Carper et al 2022) and their impacts on defensive traits across development (Carper et al 2019), and specifically the consequences of sequestration on defense against pathogens (Muchoney et al 2022). The culmination of this line of research is a large scale manipulative mesocosm experiment, to explore the eco-immunological mechanisms driving population dynamics of herbivores on alternate host plants and understand their implications for the evolution of herbivore diet breadth.

I am currently collaborating with Deane Bowers (CU-Boulder), Angela Smilanich (UNR), and Nadya Muchoney (UNR), to examine how the incorporation of a novel introduced host plant impacts interactions between herbivores and their natural enemies. A growing body of evidence suggests that the insect immune system plays a vital role in structuring interactions between plants and their insect herbivores, and humans can directly alter these relationships through introducing novel hosts, but also indirectly through host plant-mediated changes in species interactions. Together, we've studied three nymphalid butterfly species: Junonia coenia, Euphydryas phaeton, and Anartia jatrophe, all of which feed on an introduced hostplant, Plantago lanceolata. Specifically, we are exploring how this novel host shift impacts the sequestration of plant secondary metabolites, immune function, and defense against both pathogens and parasitoids. We've explored broadly variation in host plant secondary metabolites and their sequestration by herbivores (Carper et al 2022) and their impacts on defensive traits across development (Carper et al 2019), and specifically the consequences of sequestration on defense against pathogens (Muchoney et al 2022). The culmination of this line of research is a large scale manipulative mesocosm experiment, to explore the eco-immunological mechanisms driving population dynamics of herbivores on alternate host plants and understand their implications for the evolution of herbivore diet breadth.

Native Bee Ecology & Natural History

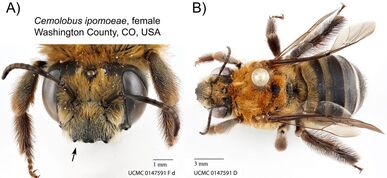

Wild bees play an integral role in both natural and agroecosystems and understanding the impacts of human environmental change on wild bee communities is paramount to both our agriculture and their conservation. I've collaborated with a number of researchers studying bee community response to human land-use. In collaboration with Mary Jamieson (Oakland University), and Deane Bowers (CU) I surveyed bees across agriculturally intensive landscapes in Eastern Colorado, greatly expanding our understanding of Colorado bee diversity (Jamieson et al 2019) and in some instances re-describing previously unknown species' distributions (Carper et al 2019). It's taken over 5 years to determine the more than 30,000 specimens collected, but we are now exploring agricultural and conservation practices that promote wild bee abundance and diversity, as well as potential risk factors for native bees is Colorado's agroecosystems. I also explored bee community response to urbanization in two of the fastest growing metropolitan regions of the country. In collaboration with Kristen Birdshire and Christy Briles (CU-Denver), we found declines in bee abundance and diversity with increasing urbanization around Denver, CO (Birdshire et al 2020). In contrast, in and around Raleigh, NC, I found that suburban developments harbored surprisingly higher abundances and diversity of bee than natural forests (Carper et al 2014). These differences no doubt reflect differences in the legacy of human land-use and underscore the need for more regional and habitat-centric studies.

Wild bees play an integral role in both natural and agroecosystems and understanding the impacts of human environmental change on wild bee communities is paramount to both our agriculture and their conservation. I've collaborated with a number of researchers studying bee community response to human land-use. In collaboration with Mary Jamieson (Oakland University), and Deane Bowers (CU) I surveyed bees across agriculturally intensive landscapes in Eastern Colorado, greatly expanding our understanding of Colorado bee diversity (Jamieson et al 2019) and in some instances re-describing previously unknown species' distributions (Carper et al 2019). It's taken over 5 years to determine the more than 30,000 specimens collected, but we are now exploring agricultural and conservation practices that promote wild bee abundance and diversity, as well as potential risk factors for native bees is Colorado's agroecosystems. I also explored bee community response to urbanization in two of the fastest growing metropolitan regions of the country. In collaboration with Kristen Birdshire and Christy Briles (CU-Denver), we found declines in bee abundance and diversity with increasing urbanization around Denver, CO (Birdshire et al 2020). In contrast, in and around Raleigh, NC, I found that suburban developments harbored surprisingly higher abundances and diversity of bee than natural forests (Carper et al 2014). These differences no doubt reflect differences in the legacy of human land-use and underscore the need for more regional and habitat-centric studies.

Plant-Pollinator Interactions

Land-use change has implications not only for pollinators but also the plants that depend on them, with varying effects on the outcome of plant-pollinator interactions (Irwin et al 2013). In collaboration with Rebecca Irwin (NCSU), Lynn Adler (UMASS-Amherst) and Paige Warren (UMASS-Amherst) I studied the impacts of urban development on pollination of three native, bee-pollinated plants: Gelsemium sempervirens, Oenothera fruticosa, and Campsis radicans. All three flowering species were pollen-limited for some measures of female plant reproduction; however, contrary to our predictions, plants growing in suburban areas were more pollen limited for both fruit and seed set (Carper et al 2022) despite having more abundant and diverse bee communities (Carper et al 2014). This was likely due to increased competition in urban areas, and indirect effects of increase heterospecific pollen deposition, underscoring the need to understand the many indirect effects land-use on species interactions.

Land-use change has implications not only for pollinators but also the plants that depend on them, with varying effects on the outcome of plant-pollinator interactions (Irwin et al 2013). In collaboration with Rebecca Irwin (NCSU), Lynn Adler (UMASS-Amherst) and Paige Warren (UMASS-Amherst) I studied the impacts of urban development on pollination of three native, bee-pollinated plants: Gelsemium sempervirens, Oenothera fruticosa, and Campsis radicans. All three flowering species were pollen-limited for some measures of female plant reproduction; however, contrary to our predictions, plants growing in suburban areas were more pollen limited for both fruit and seed set (Carper et al 2022) despite having more abundant and diverse bee communities (Carper et al 2014). This was likely due to increased competition in urban areas, and indirect effects of increase heterospecific pollen deposition, underscoring the need to understand the many indirect effects land-use on species interactions.

Floral Antagonism

Changes in land-use can also have indirect effects on other types of species interactions. Most plant species interact not only with mutualistic pollinators but also a number of antagonistic visitors. In addition to mutualist pollinators, Gelsemium also interact with floral herbivores (hereafter florivores). A greater proportion of suburban Gelsemium experience florivory which could affect pollinator visitation and be an important driver of pollen-limitation of fruit and seed set in suburban compared to natural forests. To understand the role of florivory in driving pollinator behavior, pollination, and Gelsemium reproduction, I experimentally manipulated both florivory and pollination in a common garden experiment. I found that floral damage reduced visitation to plants, and subsequently pollen donation, an estimate of male function. However, contrary to predictions floral damage had little effect on female reproduction (Carper et al 2016), suggesting that the effects of floral antagonism may have stronger consequences for male than female reproductive success.

Changes in land-use can also have indirect effects on other types of species interactions. Most plant species interact not only with mutualistic pollinators but also a number of antagonistic visitors. In addition to mutualist pollinators, Gelsemium also interact with floral herbivores (hereafter florivores). A greater proportion of suburban Gelsemium experience florivory which could affect pollinator visitation and be an important driver of pollen-limitation of fruit and seed set in suburban compared to natural forests. To understand the role of florivory in driving pollinator behavior, pollination, and Gelsemium reproduction, I experimentally manipulated both florivory and pollination in a common garden experiment. I found that floral damage reduced visitation to plants, and subsequently pollen donation, an estimate of male function. However, contrary to predictions floral damage had little effect on female reproduction (Carper et al 2016), suggesting that the effects of floral antagonism may have stronger consequences for male than female reproductive success.